Who are the unvaccinated and how can we change their minds before it's too late?

Sorting the reachable from the unreachable.

We are seeing a new coronavirus surge in the US. In response, governments have engaged in a variety of vaccine incentives, from lotteries to free marijuana to straight-up cash. Pop star Olivia Rodriguez was invited to the White House. Rapper Juvenile changed “Back That Thing Up” to “Vax That Thing Up.” These efforts have emerged in an environment in which a sizable number of Americans remain unvaccinated, allowing variants to proliferate. Hospitals are, once again, on the verge of collapse. There is a growing recognition that greater vaccination could have prevented this.

Who are the unvaccinated? Can we change their minds?

Prior to covid, the unvaccinated by choice could be sorted into two categories.

Bring in the celebrities. Bring in the clergy. Throw money at them. Give them free weed or free booze or free whatever, writes Editorial Board member Magdi Semrau.

The first group, the most well-known, is the extreme anti-vax movement. These are high-profile figures like Jenny McCarthy and Robert Kennedy, Jr., who sow doubt about even the extremely safe and effective measles vaccine. They whisper about false links to autism and the danger of mercury. In the last decade, such disinformation has proliferated on social media. This group used to be a small, extremist set who opposed vaccination with an almost religious fervor. Members of this group were not merely misinformed; they were ideologues and conspiracy theorists. Though their numbers were small, they have caused significant harm, spreading just enough doubt about vaccines to facilitate outbreaks of both measles and mumps. When it comes to public health and infectious disease, even small cracks can produce system-wide damage.

The second group of unvaccinated Americans is less well-known, but surely equally as important. They, too, existed prior to covid. Unlike the extremists, their choice was not ideological. Some were hesitant, perhaps having minor doubts. Sure, vaccines were probably safe, but were they worth it? Many more were simply complacent. To some extent, this group has people you know. Or maybe even you are a member of it.

Americans are typically good about getting their children the standard roster of shots. They take kids in for check-ups during the first years of life and, with these check-ups, come vaccines. However, as these children age, compliance decreases. In adulthood, Americans fail to get booster shots and chronically skip the annual flu vaccine.

The complacency isn’t surprising. Whereas the Silent and Boomer generations remember public pool closures, children with ravaged limbs and terrified parents, younger generations have lived in a world where infectious diseases like measles, mumps and polio have been largely eradicated in the United States. The life-threatening diseases are not distant memories for them. They just don’t exist.

Pre-covid, various people did not get vaccinated for various reasons. Some were extremists. Others were merely complacent. Post-covid, the two basic categories remain. What’s new is the sizable partisan contingent that has joined the extremists.

Public opinion polling indicates that there are two groups of Americans who are covid-unvaccinated. Kaiser Health has categorized these Americans as “Wait and See”—about 12 percent of adults—and “Definitely Not”—about 13 percent. The “Wait and See” are likely motivated by multiple factors, many of which relate to historical patterns in under-vaccination. This is apparent from their demographics.

About a third of “Wait and See” are young—18-29 years old. They are likely to perceive their personal risk to the coronavirus as low. Early in the pandemic, much reporting gave the impression that the dangers of covid were limited to the elderly and to those with pre-existing conditions. Many people regrettably absorbed this message. “Wait and See” are evenly split between Democrats and Republicans. They’re also racially and ethnically diverse: 49 percent white, 22 percent Black and 20 percent Latino.

All of this is good news. If young Americans are driven by complacency, public health campaigns can help. And Black and Latino people are not likely, historically, to be anti-vaccine extremists. They may lack access to medical care or they may experience anxiety due to the outcomes of medical racism. This, too, can be addressed through improved medical communication as well as community-level public messaging. In other words, the “Wait and See” are reachable. Their minds can be changed. We’ve already seen, as time passes, that their numbers decrease. Their numbers were greater in January than they are in July. Apparently they are actually waiting and seeing.

The “Definitely Not” group is quite a different sociopolitical beast. The overwhelming majority—70 percent—is white. Two thirds of the group identifies as Republican. Eighty-four percent are 30 or older. Members are more likely to be suburban than rural or urban. The majority (57 percent) have at least some college education. “Definitely Not” are barely budged by incentives. Whereas “Wait and See” are 14 percent more likely to get a vaccine when offered $100, willingness among “Definitely Not” increases by 1 percent. Offering other kinds of incentives produces similar results. The “Wait and See” respond to various nudges. The “Definitely Not” remain steadfast.

The “Definitely Not” thus comprise not only traditional anti-vaccine extremists, but also conservative partisans. On account of the right-wing media downplaying the risk, they may, like the “Wait and See,” perceive their risk to be low. Unlike “Wait and See,” however, they are not moved by incentives whatsoever. Like the pre-covid anti-vaxxers, their commitment to being unvaccinated has the character of a political, or even a religious belief. It is part of their personal and group identity. The conversation is not a medical one. The decision isn’t sensitive to evidence. It is deeply ideological.

What should we infer from the data? One lesson is clear enough. Many who are unvaccinated—the “Wait and See”—are reachable. What’s the best strategy? Throwing every strand of spaghetti at the wall is probably the right approach. There’s almost no risk, and the potential societal benefit is tremendous. Bring in the celebrities. Bring in the clergy. Throw money at people. Give them free weed or free booze or free whatever. Don’t give up and unless you have a better suggestion, don’t sneer at methods that may only convince 5 percent of them. Every shot in every arm matters.

What about the “Definitely Not”? Unfortunately, there is little reason to think public health efforts will make a difference. However, it is still possible things could change. Consider two recent events. The first is the arrival of the Delta variant, which now accounts for 80 percent of cases in the United States. Hospitals in Florida, Mississippi, Arkansas, Missouri, and Alabama are at or past capacity. Medical workers have returned to social media, begging people to get vaccinated and telling dire tales of deaths among the unvaccinated. And, although the data is still spotty, anecdotal reports suggest that young people may be suffering from more severe disease.

Second, conservative media and some Republican politicians have shifted their stance on vaccines. A few weeks ago, Fox was comparing vaccines to apartheid and forced sterilization. Anthony Fauci, the figurehead of American disease control, was Public Enemy No. 1. Then last week, the network changed its tune, advising viewers to get vaccinated and even praising Dr. Fauci as a fundamentally decent human.

Alabama Governor Kay Ivey, once lax about covid control, gave an angry speech declaring that the “unvaccinated folks are letting us down.” The rhetoric that bred the new partisan wave of vaccine resistance seems to be changing for the moment. Some of the “Definitely Not” may listen. Perhaps some have witnessed covid’s devastation in their communities. Maybe these factors will change the minds of the “Definitely Not.”

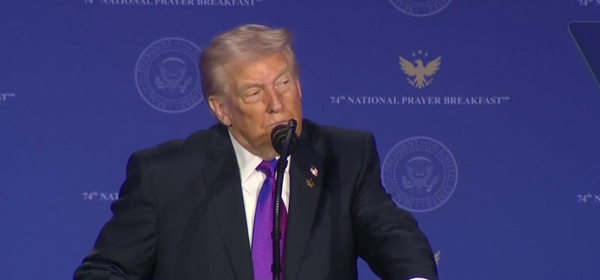

Of course, any optimism must be measured. The GOP is still opportunistic, willing to tolerate loss of life for a victory in the culture war. And Trump is still Trump. Just last week, as Fox pivoted toward being pro-vaccine, Trump announced his followers were vaccine-hesitant because they did not believe the election was legitimate. He more firmly tied vaccine hostility to partisanship. We should expect that, if such antipathy benefits Trump in the slightest, he’ll continue to promote it even as bodies pile up.

—Magdi Semrau

Born and raised in Alaska, Magdi Semrau is a writer now pursuing graduate work in linguistics, communication sciences and disorders. Follow her on Twitter @magi_jay.